Okay, this week I received my manuscript for Speaking Ill of the Dead: Jerks in Connecticut History (available for pre-order from Amazon, by the way) for what should be close to the final round of editing.

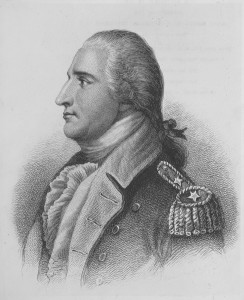

Here’s a rayality exclusive excerpt from Chapter 1, “BENEDICT ARNOLD: FROM HERO TO TRAITOR TO SCOURGE” (Not the chapter title I suggested, for the record.) I really like Arnold’s story because many people don’t realize that up until the moment he turned traitor, he was arguably the biggest hero of the American revolution, which made his treachery even more devastating.

Here’s a rayality exclusive excerpt from Chapter 1, “BENEDICT ARNOLD: FROM HERO TO TRAITOR TO SCOURGE” (Not the chapter title I suggested, for the record.) I really like Arnold’s story because many people don’t realize that up until the moment he turned traitor, he was arguably the biggest hero of the American revolution, which made his treachery even more devastating.

This excerpt covers to an extent how Arnold gained that “hero” reputation.

Oh, and keep in mind this is still in the process of being edited, so it may change by the time you read it in print.

Although being recognized by many high-ranking officers for his valor and leadership, Arnold reached a breaking point when in February 1777 the Continental Congress promoted five junior officers over him. Enraged, he set out for Philadelphia to address the situation.

Being a man of action, however, Arnold couldn’t stand idly by whenever there was a scrap to be had. After learning of a British attack on Danbury while on a brief visit in New Haven, he immediately rode to the scene to lead the local forces in a counterattack that would become known as the Battle of Ridgefield. During the fight, his horse was shot out from under him and landed on his bad leg, further aggravating his old wound. While pinned under his horse, he was also nearly captured, but managed to fend off his attackers and escape. Even after having a second horse shot out from under him during the engagement, Arnold was able to lead his Connecticut countrymen in repelling the British, inflicting heavy enemy losses.

His most bitter enemies in the Continental Congress couldn’t deny his part in the victory, and begrudgingly promoted Arnold to major general, which was a step up, but not to the level that he felt was commensurate with his performance. Rather than indulge in petty behind-the-scenes politics, he believed his on-the-battlefield successes should speak for themselves. Commander-in-Chief George Washington tried to intercede on Arnold’s behalf, submitting a letter to the Continental Congress stating, “It is needless to say anything of this gentleman’s military character. It is universally known that he has always distinguished himself as a judicious, brave officer of great activity, enterprise and perseverance.” The letter was ignored.

After the failure of Washington’s recommendation, Arnold decided that he’d had enough of political games.

Timing is everything, however, and on July 11, 1777, just as Arnold was going to deliver his formal resignation, word came that Fort Ticonderoga had fallen back into British control. Again, despite the perceived insult from the Continental Congress, Arnold could not help himself when Washington offered him an opportunity to return to battle. Bad feelings were put aside (temporarily) and, still miffed, Arnold quickly made his way back to upstate New York.

Once there, Arnold found himself in the middle of another personality clash, this time between Continental Army generals Horatio Gates and Philip Schuyler. He threw his support behind Schuyler, which did not particularly endear himself to Gates and would soon cause him more angst.

Arnold’s first task was to retake nearby Fort Stanwix, for which he was given nine hundred men. The British had far superior numbers, but through a cunning ruse, Arnold made them believe that his force was the larger. Not wanting to risk a major defeat, the Redcoats quickly withdrew. Arnold took the fort with no resistance, and mission accomplished, returned to the main force.

However, the army gathered was now under the full command of Gates, and the assertive Arnold regularly clashed with the conservative general, a situation that came to a head at the end of October 1777 in Saratoga. During the Battle of Freeman’s Farm, Arnold had favored taking the attack to the British, under the command of General John Burgoyne, while Gates had wanted to strike a more defensive stance. During the early part of the multiday engagement, Arnold discovered that Gates was not only countermanding Arnold’s orders, but was also sending reports to the Continental Congress discrediting Arnold’s contributions. He confronted Gates through a series of angry letters, which of course, were not well received. Gates immediately relieved Arnold of his command for insubordination.

Incensed, Arnold was ready to leave Saratoga, but his fellow officers recognized that his battlefield leadership was desperately needed with “Granny” Gates in charge, and signed a petition requesting he stay. Arnold relented and remained, which would become a momentous decision.

Pride wounded and beside himself, Arnold fumed in his tent as the Battle of Bemis Heights began to unfold. Forbidden to participate, he tried to keep abreast of the fight, but watching was near maddening. Finally, unable to stand idly by any longer while the skirmish continued all around him—he could see Gates sitting in his own tent, quietly minding the action from the sidelines— Arnold burst forth from his tent, leapt on his black stallion, Warren, and thundered into the fight.

Keep in mind that Arnold’s traitorous actions were still in the future—at this point, the sight of the fiery patriot ignoring what seemed like timid orders, calling any brave men who would follow him into the fray, and then riding right into the fury of the British assault, was stirring. Sometimes being a jerk can be a benefit, and this was one of those moments. Ignoring the fact that he had no official command, the troops fell in behind the impassioned Arnold as he led a bold strike at the heart of the British lines.

It worked. Spurred on by Arnold at the head of the charge atop his faithful steed, sword aloft and bellowing orders while bullets and cannonballs whizzed past, the American forces rallied and began to turn back the Redcoats.

Victory at hand, Arnold crashed through the enemy line and personally took the fight to the British. His mount was shot out from under him, but undeterred, Arnold continued his frenzied attack. A bullet soon felled him, however, striking his troubled leg. Badly wounded yet still exhorting his men on, he finally yielded so that he could be dragged off the battlefield.

Even though Arnold had fallen, the now-inspired Americans did not, and the day’s victory was the beginning of the end for the British in upstate New York. Ten days after Arnold’s stunning act of bravery in the Battle of Saratoga, Burgoyne surrendered, a key turning point in the war—France decided to lend much-needed support to the fledgling country and its revolution against the English crown.

Because of Arnold’s undisputed courage at Saratoga, however, the Continental Congress had no choice but to award Arnold the full promotion and recognition that he had previously been seeking. If at that point he had simply gone home fully vindicated and spent the rest of the war healing from his wounds—which had essentially crippled him—he’d be remembered as one of the great heroes in American history.

Being a jerk, however, Benedict Arnold couldn’t leave well enough alone. . . .

Again, Speaking Ill of the Dead: Jerks in Connecticut History is available for pre-order from Amazon. It will be in bookstores in September. I’m sure I’ll *probably* mention this again between now and then.

Unsubstantiated drivel … and not nearly as funny as F Troop!

I can’t wait to read the book!

[…] an excerpt from Chapter 9, entitled “P.T. Barnum, Prince of the Humbugs.” (Again, as with the Benedict Arnold chapter, this was not the title I chose, but the one the publisher picked. My original was “P.T. […]

[…] 1780. The HMS Vulture was the British ship that had sailed up the Hudson to aid Connecticut jerk Benedict Arnold in his escape after his treachery was exposed. Although you can’t see the river from here […]